This store requires javascript to be enabled for some features to work correctly.

coming soon!

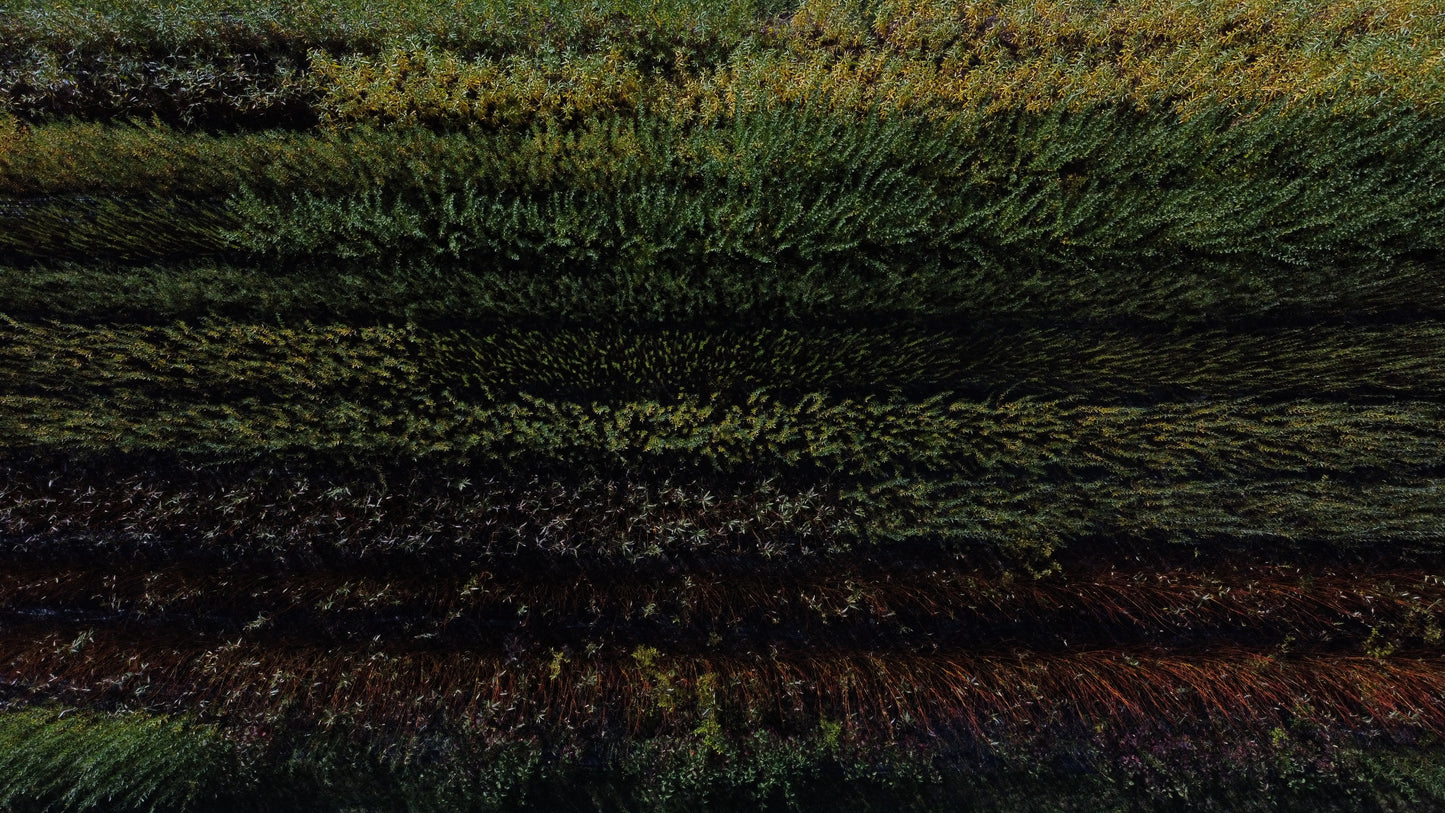

farm grown willow baskets

We cultivate willow on our farm and weave beautiful, functional baskets. Willow baskets coming soon online and at the Ithaca Farmers Market in spring 2024! Until then, purchase your cuttings from our farm website to start your own willow patch

Salix x fragilis 'Natural Red'

Salix purpurea 'Dicky Meadows'